When Jesus washed the feet of his disciples, he stressed the importance of what he was doing. Likewise, when he passed the bread and the wine, he stressed the importance of what he was doing. Both acts were to be remembered and done in memory of Jesus. And both are to this day, although the footwashing is not anywhere near as common as the eating and drinking of the bread and wine.

What is it about the footwashing that has put it into a very low second place? Logistics may have something to do with it but a look at its meaning, the sign that Jesus is giving us, probably has a lot more to do with our not even talking about it all that much. In the Greco-Roman world, it was slaves who washed the feet of their masters and their masters’ guests. That Jesus would do the work of a slave must have been shocking at the time and still is, if we consider the implication that imitating Jesus’ act is not confined to literally washing the feet of others but entails acting as a slave to others. Fundamentally, being a slave means to be in the hands of another person. If we are supposed to put ourselves into the hands of others like this, what does this say about trying to enslave another human being? Jesus himself was about to put himself into the hands of others with the result that he would be crucified. If the disciples still remembered the anointing of the feet of Jesus by Mary of Bethany six days ago, that too would have added to their discomfort. This discomfort extends to the parallel versions of this story

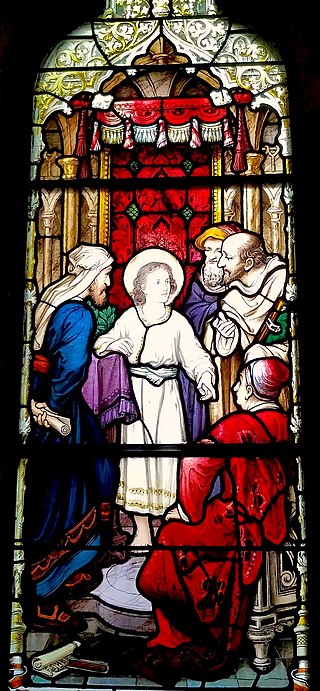

The woman ( or women) in the Gospel stories poured out her very substance (the expense of the perfume or oil) in devotion to Jesus. Likewise, Jesus poured out his very self to his disciples in washing their feet just as he was about to pour out his life for all people to put an end to the violence that includes the enslaving of other people. In those Gospel stories, the women were commended as examples of discipleship. If Jesus thought these women were such good examples, it makes sense that Jesus was humble enough to learn from them and do for his disciples what the women had done for him. There is no indication in any variant of the story that the disciples were reconciled to what the women had done. Did Peter take umbrage at Jesus for washing his feet because he associated it with the women as much as he associated it with slavery?

With the bread and wine, Jesus again poured himself into the two elements just as he poured out his life on the cross. So it is that the footwashing and the Eucharist both mean the same thing. We have put up with the Eucharist more than the footwashing because we have been able to sidestep this meaning by arguing about the metaphysics of Jesus’ presence. But the real presence of Jesus is his pouring himself into the hands of others and through them, the hands of his heavenly Abba. Paul knew this very well but we also conveniently forget that the context of his recalling the Last Supper is to upbraid the Corinthians for violating its meaning through denigrating the weaker and poorer members of the assembly.

Jesus rebuked Peter for refusing to have his feet washed, warning him that he would have no share in him. (Jn. 13: 8) This warning converts Peter so powerfully that he goes overboard and asks to be washed all over. He has allowed Jesus to be a slave to him so that he could be a slave to Jesus and all people. This conversion did not prevent him from denying Jesus three times but it allowed him to hear the cock crow and then to affirm his love to the Resurrected Jesus three times. This is what both the footwashing and the Eucharist are all about.