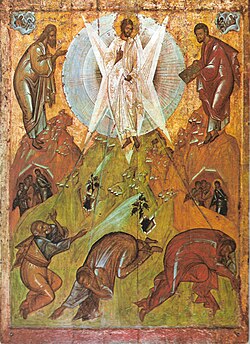

The story of the Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor is as disorienting as it is blinding. It was also disorienting and blinding for the three apostles Jesus had taken up with him. Obviously, Peter didn’t know what to say, so we shouldn’t feel bad if we don’t know what to say, either.

One of the more fascinating and powerful reflections on this story is at the heart of the theology of the 14th century Greek theologian St. Gregory Palamas. He suggested that the light of Tabor was the working of the uncreated energies of God. This energetic light, the Light of Tabor, embodies God’s self-giving to us, a giving of Godself, that is deification. Not human self-deification, but deification as a gift from God who gives us everything that God has. This concept hasn’t gained much traction in Western Christianity, partly because it doesn’t compute well with many forms of Western theology. However, for those who find traditional Western theology problematic, the Palamite notion is perhaps an attractive alternative. For what it’s worth, I think the clash between Western and Palamite notions explodes into a powerful mystery which is deeper than one set of concepts alone.

There is much more to the radiance than blinding brilliance. The Hebrew word kabod, also means glory in the sense of honor. This is also true of the Greek word doxa that translates the Hebrew. When we glorify a human being for great accomplishments, there is a sort of radiance we put around them. Saints are often painted with a nimbus when portrayed in art. However, there is a tension at the root of glorification. It almost always seems to be accompanied by derision and dishonor. In fact, the Greek word doxa means dishonor as much as it means honor. The people we honor by putting on a pedestal are knocked over in a heartbeat if they don’t meet our expectations. Artists like Igor Stravinsky and Bob Dylan have both been greatly honored, but both were denigrated when they changed their artistic visions away from projected expectations. This is what happens when fans make idols of the people they adore; they create little boxes to put them in.

What about Jesus? Jesus had received much glory and honor from his numerous followers, not least the three disciples who Jesus took up the mountain with him. But the more some praised Jesus, the more energetically others denounced him. In all three synoptic Gospels, the Transfiguration marks a turning point where Jesus heads towards Jerusalem where he will be denounced, mocked, and crucified. The honor given Jesus turns to dishonor. What about the disciples who experienced the Transfiguration? When Jesus told them what was coming, they resisted Jesus’ resolve and argued among each other as to who was the greatest. I can’t help but suspect that they were basking in the derived honor given Jesus up to that point and, rather than receiving glory from God, wanted to receive glory from the other followers of Jesus. Like modern day fans of celebrities, they were putting Jesus into boxes of their own making, turning Jesus into an idol. The disciples were blinded by their warped understanding of honor at least as much as they were blinded by the brilliance of Jesus’ shining garments.

We can gain more insight into glory by reflecting on the presence of Moses and Elijah with Jesus on the mountain. They were the two most glorified figures in Jewish history. Moses, by receiving the Law on Mount Sinai from God himself shone with the reflection of God ‘s light to the extent that he had to wear a veil. Elijah was the greatest of prophets. Both, however, also experienced dishonor. Several times the people threatened to stone Moses, and Elijah was a fugitive from royal power. Both were implicated in violence, especially Elijah in his contest with the prophets of Baal. They were in the position to know well what was going to happen to Jesus. Moses’ best moments, when he was most Christlike, was when he was interceding for the people to turn God’s wrath from them, even when the same people were directing wrath at him. Elijah, alone in a cave, heard God in the sheer silence of the wilderness. As for Jesus’ disciples, the Book of Acts shows them breaking out of the idolatrous boxes they had made and acting like their Master in self-giving, preaching, and healing, the divine energies clearly working through them.

There is reason to believe that the Transfiguration of Jesus was, at least in part, to prepare the disciples for the suffering Jesus would have to endure, and that they, too, would have to endure. At a deeper level, they were being prepared for the challenges of the Resurrection Life of Jesus that would energize them when the time came. As we prepare for Lent, perhaps we can make it our Lenten project to let the light of the transfigured Christ reveal our own warped notions of honor and dishonor so that the divine energies championed by Gregory Palamas can energize prayer on behalf of other people, especially those who dishonor God, a prayer enveloped in sheer silence.