After deflecting several questions from the Pharisees, Jesus poses a question of his own:” What about the Messiah? Whose son is he?” (Mt. 22: 42) Predictably they answer: “The Son of David.” That was a standard assumption at the time. Then Jesus quotes the opening verses of Psalm 110 with its Messianic overtones. Since David was believed to be the Psalmist and to be speaking to the Messiah, Jesus asks how David can call his own son “Lord?” The Pharisees can’t answer the question and, typically, Jesus doesn’t answer it either, but lets the question hang. The question has been hanging ever since.

It seems likely that Jesus was questioning the notion of a Davidic messiah who would do what David did—win lots of battles against Israel’s enemies. As Jesus became more and more aware that he was the Messiah, the question became: What kind of a Messiah should he be? If the prevailing notion of a Davidic Messiah was not it his calling, what was his calling?

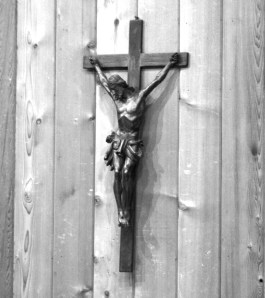

The question posed to Jesus immediately preceding the dialogue about the Messiah, asking him what the greatest commandment was, and the answer Jesus gave to that question, suggests an alternative understanding of the Messiah that Jesus was beginning to arrive at. It seems that Jesus was beginning to think he was the “Lord” addressed by David. This lead to the question: what kind of Lord should he be? Should he be a Lord whom other people were supposed to love with full heart, soul, and mind? Or was Jesus, as Lord, also to love his Lord, his heavenly Abba, with full heart, soul, and mind? This thought hints at what became known later as a high Christology, that is a Christology that affirms the divinity of Jesus. That Jesus, divine as he himself was, would turn to his heavenly Abba for guidance suggests Jesus was more interested in honoring his heavenly Abba than he was in being an object of adoration. As it turned out, Jesus learned what was at stake in loving his heavenly Abba with full heart, soul, and mind at Gethsemane. Here, Jesus, Lord as he was, was a Messiah who was deeply vulnerable as a human.

The second great commandment that Jesus cited was taken from Leviticus: the love of neighbor as oneself. (Lev. 19: 18) In Leviticus, this commandment, along with several others in the list, is framed by the Lordship of Yahweh. What is most striking about the great commandment in Leviticus is that it is in the context of not seeking revenge or bearing a grudge. The Davidic model, of course, is all about bearing a grudge against Israel’s enemies and seeking revenge against them in battle. In this verse in Leviticus, Jesus was seeing a different model for the Messiah: one who shares his heavenly Abba’s love for all people and in this love, will forswear revenge when he is killed and raised from the dead. Not what the Pharisees seemed to have been looking for.

When Paul came to see that Jesus was the Messiah, did he see a Davidic Messiah? The way he presents himself to the Thessalonians is a resounding No. Far from seeking praise from others, he cared for them as a nursing mother cares for her children. (Thess. 2: 6–8) Moreover, he suffered persecution as they suffered persecution. Sounds like he modeled himself on the way Jesus came to understand his messiahship in terms of following the two great commandments.