In Christian devotion (and in many other religious traditions as well) there is much praise to God for creating the world. That God would consider it worth while to make a world with living creatures in it is astounding; an occasion for contemplative awe. According to the Psalter, the rivers clap their hands and the mountains sing together for joy. (Ps. 98: 8) Needless to say, the Psalmist expects humans to praise God at least as much as that if not more.

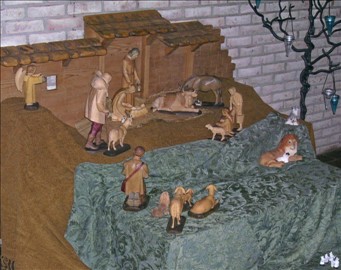

The traditional celebration of the Christ Child is enriched by the inclusion of nature. It is true that Luke doesn’t mention animals except for the sheep tended by the shepherds, but where there is a manger, there are animals, and the Magi probably didn’t walk great distances when camels were available. The tradition of farm animals being present to welcome Jesus into the world is inspired by the words of Isaiah: “The ox knows its master, the donkey its owner’s manger, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand.” (Is. 1: 3) Isaiah obviously thinks the animals are better at praising God than humans. Meanwhile, the angels really show us how to whoop it up over the pastures where the shepherds are tending their flock.

It is amazing that in spite of all the human failure to praise and obey God, the Creator entered God’s own creation as a human being, as frail as any other. That is quite a lot of downward mobility for one in whom “all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities.” (Col. 1: 16) It really is too much for us to take in. Like Mary, we need to treasure these things and ponder them in our hearts. (Lk. 2: 19)

In addition to all the carols about ox and ass tending the baby Jesus and the lovely carol Angels We Have Heard on High, there seem to be more Christmas lullabies than there are stars in the sky. The lullaby for Jesus, Schlaf, mein Jesu,” (Sleep my Jesus) sung by the alto soloist in Bach’s Christmas Oratorio is among the most beautiful. As a choir boy, I sang several lullaby carols. One of my favorites was a Czech carol called the “Rocking Carol” with flowing melodic lines accompanying the lovely melody.

From the dawn of humanity, mothers have been lulling their babies to sleep. It seems quite possible that lullabies may be among the oldest songs conceived by humanity. They are among the first songs that children learn. I still remember several from early childhood, especially the Irish lullaby: “Too-ra-loo-ra-loo-rah.” It is both fitting and a deeply sound intuition to assume that the infant Jesus would have been lulled to sleep like every other baby, his divinity notwithstanding. Nothing could more deeply affirm his full humanity. The lullaby Christmas carols give us entry into a devotion of rocking Jesus to sleep as an act of devotion.

Because God became a child who was lulled to sleep, every child is Jesus, just as each person is the least (and therefor the most) of his brethren. Like every baby, Jesus was fragile and needed to be handled with care. When he grew up, nails could be driven into his hands just as easily as with any other human. Because of Jesus, every baby, every person, needs to be handled with the same gentle care expressed in these Christmas lullabies. The same applies to the whole eco-system, which is both resilient and frail, so that heaven and nature can have something to sing about. Quite a lot for us, like Mary, to ponder in our hearts.

Czech Rocking Caro lhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wpa2qjIxolY