Jesus sternly admonished his disciples to listen when he said: “There is nothing outside a person that by going in can defile, but the things that come out are what defile.” (Mk. 7: 15) Surely Jesus wants us to sit up and take notice and think about this. We often worry about what we take into ourselves and there are good reasons for that. After all, there are foods that really are bad for us and there is much in the media that is also bad for us. In the broader conversation in this chapter in Mark, Jesus is calling attention to the ways we let certain externalities of observance distract us from inner and weightier matters. With the long history of censorship in many cultures, Jesus’ words raise the question of whether a preoccupation with what one reads or hears, although worthy of concern, doesn’t also distract one from the truth that is within. If the French thinker René Girard is right about the ongoing influence of the desires of other people on each one of us, then we are indeed ingesting much from our environment, some of it good, but some of it not so good. It’s hard enough to censor books; it is impossible to censor the impact of other peoples’s desires on each of us.

Jesus draws our attention away from what we take into ourselves to what we actually find within ourselves. What do we find there that might come out of us? Jesus says that it is from within the heart “that evil intentions come: fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, folly.” (Mk. 7: 21-22) Most of us feel defiled when we find such things within ourselves, but Jesus is telling us that we aren’t defiled by the avarice and wickedness within unless we let it out. Then and only then are we defiled by these things. Did these things, or at least some of them, come from without? Maybe. Girard’s notion that we resonate with the desires of other people suggests that is likely the case. But that is not the issue. The question isn’t where these evil thoughts come from, but what we do with them.

In his Epistle, James applies these words that he himself heard straight from Jesus. The anger that we find within ourselves “does not produce God’s righteousness.” (James 1: 20) We should rid ourselves of the “sordidness and rank growth of wickedness, and welcome with meekness the implanted word that has the power to save your souls.” (James 1: 21) Because he heard the words of Jesus and planted them in his heart, James finds other, more positive things within that he can bring out instead of the wickedness inside. If we take in many dysfunctional desires from other people, it makes sense that we would also take in many noble desires as well, such as a desire to pull an ox or a child from a pit, or give a loaf of bread or fish instead of a stone. There are many other good things that can come out of us that make us and others good and holy. All the more reason to consider carefully what we say and do that other people will take in.

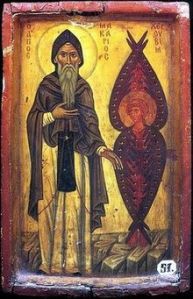

These reflections call to mind one of the most important ascetical practices of the early monastic movement: watchfulness, vigilance, the examination of thoughts. It was said of one desert monastic that he would examine his thoughts for an hour before going off to the Sunday worship gathering. Surely this practice was inspired by scripture passages such as this chapter in Mark. As Jesus’ warning suggests, this practice can be unpleasant, humbling, humiliating. But seeing what is within through watchfulness turns out to be a good way to keep what we see from coming out of us. One of the more puzzling stories from the desert movement is about a monastic who tells a troubled disciple that if he is not thinking of fornication, it means he is doing it. These words seem counter-intuitive and absurd, but this chapter in Mark gives us cause to think again. What if we don’t examine our thoughts to see what is within us? For one thing, we project what is within on others and demonize others for what is actually within us. For another, when we don’t examine that which is within us, these very thoughts can escape much more easily and we don’t even realize it because we are busy blaming other people for what we are doing without knowing it. Moses the Black, one of the most famous of the desert monastics, was asked to come to judge a delinquent monastic. He carried a leaky basket full of sand behind his back to the gathering. When questioned, he said that his sins were likewise falling behind him where he could not see them, and he was supposed to judge another. So it is that Moses the Black would counsel us, like Jesus, to remove the beam in my own eye before trying to remove a speck from the eye of another.