The Christmas season is a time when we celebrate many wonders wrought by God, not least the birth of Jesus, the Son of God, the Logos. Among the many marvels performed by God in the past are the deliverance of the Israelites from the Egyptians at the Red Sea and the return of the Israelites from the Babylonian exile. Jeremiah, who prophesied the defeat and subsequent exile, and earned himself the reputation of being a most gloomy prophet, suddenly became unbuttoned in his excitement over the return that he knew God would bring about: “Sing aloud with gladness for Jacob, and raise shouts for the chief of the nations.” (Jer. 3: 7) Jeremiah goes on to exult that the blind and the lame and the women in labor would all be returning with great rejoicing. The joy of the returning exiles “radiant over the goodness of the Lord” spills over into the Christmas celebration. Surely the God who had done such a great wonder as to bring the exiles back home had many other wonders up God’s sleeve. But who could have guessed that the wonder would be a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger?

In his Epistle to the Ephesians, St. Paul says that God “has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places,” (Eph. 3: 3) that God has “destined us for adoption” as God’s sons and daughters. As if the wonders of the Return from Exile and the birth of Jesus were not enough, God has a plan that in the fulness of time God will gather all things in heaven and earth in God .

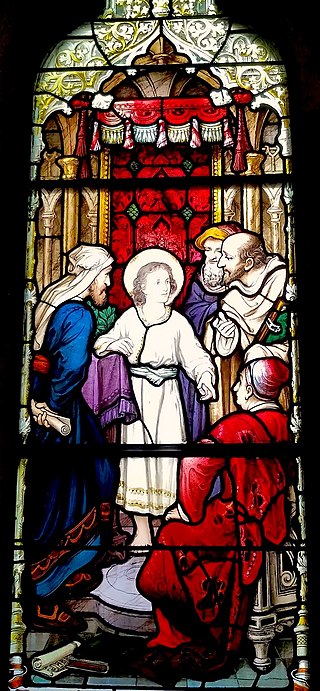

Compared to the drama of the return from the Babylonian Exile and St. Paul’s excited proclamation of God’s plan to adopt all of us as sons and daughters through God’s Son Jesus, the story of Jesus in the Temple at the age of twelve seems relatively prosaic, for all of the story’s charm and hints of mystery. (Lk. 2: 41-52) It is common for parents to have anxious moments when they don’t know where their child is, although it doesn’t feel common, let alone routine, at the time. The story shows Jesus as a typical boy in the sense of needing to begin finding his own way in life, building on what his parents have taught him, but going beyond that.

It is important to realize, however, that this very human event is part of the cosmic drama announced by St. Paul. God is reconciling the world by sending God’s Son into the world, and reconciling the world involves living through the stages of growth as a human being. This may be the only story of Jesus’ youth, but it tells us all we need to know about Jesus’ feeling his way from childhood to adolescence and on to adulthood. The earthly life of Jesus, then, gives the concrete lives of each of us the same cosmic importance. As Jesus seeks to grow in wisdom, Jesus leads us in our search for wisdom, to fulfill St. Paul’s prayer: that we will come to know the riches of God’s glorious inheritance among the saints and the immeasurable greatness of God’s power. (Eph. 1: 18–19)

The image of Mary holding her Child is arguably the defining image of the Christmas season. Its tenderness is comforting in a world where violence against the most vulnerable dominates the news. Vulnerability, such as that of a newborn baby tends to arouse either a gentle wish to nurture and protect, or it sets off an urge to take advantage of weakness in hard-hearted fashion as Herod did. We see both of these tendencies happening in the world about us and it is possible that we struggle between them within ourselves. If we let ourselves get caught up in the frantic conflicts occurring today, any weaknesses we see in our opponents become targets for increased aggression.

The image of Mary holding her Child is arguably the defining image of the Christmas season. Its tenderness is comforting in a world where violence against the most vulnerable dominates the news. Vulnerability, such as that of a newborn baby tends to arouse either a gentle wish to nurture and protect, or it sets off an urge to take advantage of weakness in hard-hearted fashion as Herod did. We see both of these tendencies happening in the world about us and it is possible that we struggle between them within ourselves. If we let ourselves get caught up in the frantic conflicts occurring today, any weaknesses we see in our opponents become targets for increased aggression. Tonight, we celebrate the birth of a child. Usually, there is rejoicing when a child is born. One of my family stories is that my grandmother was so excited about my birth that she burned two pots of beans.

Tonight, we celebrate the birth of a child. Usually, there is rejoicing when a child is born. One of my family stories is that my grandmother was so excited about my birth that she burned two pots of beans. The angels say to the shepherds: “Do not be afraid.” (Luke 2:10) They say the same to us today. What are we afraid of? The shepherds were afraid of the glory of the Lord shining about them. That sounds like a good thing, but most of us aren’t used to glorious light filling the night sky any more than the shepherds were. Even the most devout of us would at least be startled if such a light shone around us. When Herod heard of the birth of a child destined to be a king, he was afraid. Caesar Augustus would have been as afraid if he had been told about Jesus’ birth. His successors were sufficiently afraid to persecute the followers of Jesus for three centuries. What were they afraid of?

The angels say to the shepherds: “Do not be afraid.” (Luke 2:10) They say the same to us today. What are we afraid of? The shepherds were afraid of the glory of the Lord shining about them. That sounds like a good thing, but most of us aren’t used to glorious light filling the night sky any more than the shepherds were. Even the most devout of us would at least be startled if such a light shone around us. When Herod heard of the birth of a child destined to be a king, he was afraid. Caesar Augustus would have been as afraid if he had been told about Jesus’ birth. His successors were sufficiently afraid to persecute the followers of Jesus for three centuries. What were they afraid of?