We all like a story that ends happily with the loose ends tied together in satisfying ways. It makes us feel good, especially if the good guys had to overcome the machinations of the bad guys and the bad guys got what they deserved. Likewise, a symphony that ends triumphantly raises our spirits. The only thing wrong with these things is that real life isn’t like that. Yes, there are happy and satisfying moments and what we might call mini-happy endings, but happily ever after isn’t a sure thing, as Sondheim showed in his musical Into the Woods where we see just how grim the ever after can be. (Among many other things, Cinderella’s marriage with Prince Charming is on the rocks.) These thoughts suggest that the feel-good happy endings are illusory. The hard reality of real life can feel all the harder for it. A more positive way to look at it is to take the happy endings eschatologically. In God’s good time, everything really will be worked out. There is much comfort in this hope and it is fundamental to the Christian vision, but sometimes we need more direct and realistic encouragement and hope along the way. Sometimes an ending to a story that doesn’t resolve everything or even anything, or a symphony that ends with chords that hang in the ear, is actually more comforting (The sixth and ninth symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams are good examples of this.)

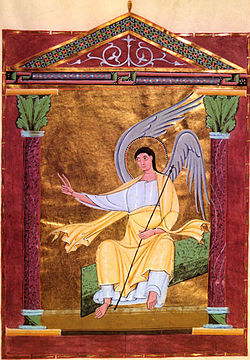

Easter Sunday tends to be celebrated as the ultimate happy ending. Yes, Jesus suffered a horrible death, but he came through alive and well and happy and the gates of eternal life have been opened to everybody. But with a lectionary that gives us Mark’s Resurrection story every three years, we get something very different. It ends with a group of frightened women running away from the empty tomb in spite of the angel’s announcement of Jesus’ Resurrection. All this after a totally bleak account of a god-forsaken Christ dying on the cross. What kind of happy ending is this? From the earliest Christian centuries to the present day many have had trouble believing Mark would end his Gospel this way. That is why there are a couple of additions clumsily attached to the end that don’t even remotely match the style of Mark’s writing and outlook.

For those of us who feel better with a happy ending, Mark is a real downer. But the advantage of an unresolved ending is that it can give us pause to think about some things we might not think about if blinded by a happy ending. The frightened women running from the empty tomb make it clear that the strife indeed isn’t over and the battle isn’t done as many horrifying current events make clear. The women thought they would anoint the dead body of Jesus, but that didn’t happen. Ending the Gospel with the women anointing the body to match the anointing of Jesus’ head at the house of Simon the Leper just before the passion would have been a satisfying bittersweet ending. But we don’t ever get that. So what hope do we get from the frightened women?

For one thing, a big thing, if we don’t really know what to make of the Resurrection, if we aren’t sure what it really means for our lives, we can take heart from these women who also didn’t know what to make of it. If we feel flat-footed and flat-brained about the Resurrection, these women in their awkward, frightened flight were obviously flat-footed and flat-brained themselves. This can give us space to ask ourselves what it really does mean that Jesus is risen from the dead. How do we live with a Jesus who died but who isn’t dead after all and is very much alive here and now? When we ask ourselves these questions, the answers are hardly obvious and we are then in a position to let the questions linger rather than prematurely clutching at a fully resolved happy ending.

Mulling over these questions can help us notice that the other Gospels also leave unresolved cracks in their narrations of the Resurrection. In Matthew and Luke, where the women are reported to have told the other disciples about the empty tomb and the angel’s message, the disciples think the women are out of their minds. Nobody seems to recognize Jesus at first when he appears. Why? The moving story of the journey to Emmaus is especially illuminating. The two disciples on the road are downcast, not the least cheered up by the rumors of what the women had said. But at least they are asking questions and this gives Jesus the opportunity to lead them into further insight as to what has happened. The story of Jesus becoming recognizable in the breaking of the bread and then disappearing leaves us hanging, but it leaves room for more to come. These disciples who listened to Jesus as he opened the scriptures to them have much more to learn and to look forward to, even if they don’t know what all of it is.

The ending in Mark is so abrupt because it isn’t really the end. It is the beginning. Galilee is where the story began. The disciples are told to go back and make a new start and we are told to do the same. The obtuseness and cowardice of the disciples throughout the Gospel aren’t the last word after all. Jesus isn’t finished with them and he isn’t finished with us either. Forgiveness is sneaking in right when we weren’t expecting it. With the stage cleared of Jesus, the disciples, the women, we are all that is left with the angel to prod us on. This Gospel is our story now and it will never have an end any more than the Risen Christ has an end. Will we return to the beginning of the story and live it ourselves? Let us sit quietly with the risen Christ with all our puzzlement and disorientation and prayerfully let the Risen Lord fill our hearts and minds with the Risen Life.