The brief story of the widow putting two small coins into the temple treasury, the only coins she had to live on, has often been touted as an edifying story about sacrificial generosity. I’ve come to seriously doubt that Jesus intends us to see it that way. Yes, the woman is generous and one can think of her many successors who built St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York with their hard-earned pennies. But just before the woman comes with her two small coins, Jesus has castigated the scribes who “devour widows’ houses.” Moses and the prophets constantly championed the widows and orphans, and yet a person who is supposed to be championed is instead devoured by the system. What Jesus knew and the poor widow didn’t, is that the temple was a lost cause; it was going to be destroyed.

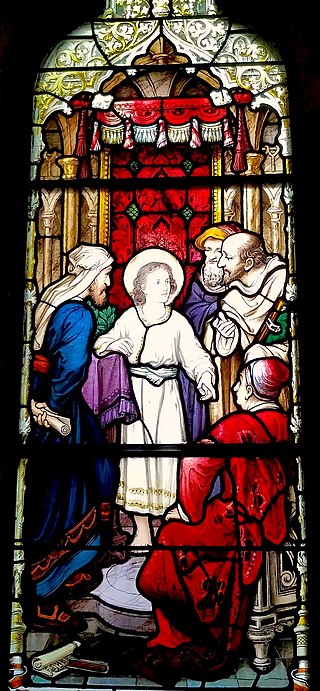

But Jesus also knew that the temple was a holy place. Hence his fury that it had been turned into a den of thieves. When Jesus was a child, he knew that the temple was the place where he should be about his Father’s business. (Lk. 2: 49) Religious anthropologists know very well that there is a human need for sacred space, space that focuses one on God and makes one feel closer to God. Hence the devotion of the poor widow in Jerusalem and the widows and other people with meager resources donating towards the building of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The destruction of the temple in 70 A.D. was a shock to both the Jewish and Christian communities and both communities had to build their traditions out of the ruins. After all, the first followers of Jesus also worshiped in the temple when it was still extant. The Jews recreated their tradition by embodying the Temple sacrifices through their daily practice developed in the Talmud. As for Christianity, John, in his Gospel, quoted Jesus as saying that if the temple should be destroyed, he could rebuild it in three days, meaning, as John goes on to say, that Jesus was referring to his body as the real Temple. (Jn. 2: 19–21) The author of Hebrews picks up this theme. By being the once-and-for-all offering for sin, Jesus has replaced the temple where sin offerings were made, with his own body. (Heb. 9: 24–28) For Christians, then, the temple has been replaced by Jesus as the focal point, the sacred space. But if Jesus has entered the heavenly sanctuary not made by human hands, as the author of Hebrews says, then where does a Christian find holy space?

Over the centuries, many church buildings have been built to fulfill this need, some of them overwhelming cathedrals, others storefronts. For me, one of the most moving entries into sacred space was a modest building, unadorned except for a cross strategically placed so as to be hard to notice, with a worn linoleum floor inside. But this is where a small group of Christians had worshiped for years in East Germany. These people had spent their whole lives giving up two small coins in their worship of God.

But, as the Risen Jesus revealing himself in the breaking of the bread shows, Jesus, is not only the true Temple of God but he makes all of us into the Temple that is His Body. That is why Paul, in line with John and the author of Hebrews, says that we are made the Temple of God by and in Christ. (1 Cor. 3: 16) Just as Jesus is the Temple by giving his whole life, we are part of the same Temple when we give all of our lives to God and neighbor. That is, the temple of God is everywhere as is the case in the Book of Revelation, where there is no temple because the Lamb has become the Temple. (Rev. 21: 220 At St. Gregory’s, it strengthens our prayerful focus on God to have the abbey church to go to several times a day, just as it helps to have set times for prayer to help us cultivate an attitude of prayer at all times. When we had a couple of weeks when we couldn’t pray in the church because the furnace had broken down, I missed the sense of focus the church gives us. But it is at least as important not to imprison our prayerful focus on God in a church space, but to keep the walls permeable to the rest of the world so that we are always in God’s Temple because we are God’s Temple. As the true Temple, Jesus broke bread at an inn just as we break bread at the Eucharist in the church.

See also: God’s Kingdom in Two Small Coins

It is significant that Jesus had wandered over to Caesarea Philippi, deep in imperial territory, before asking his disciples who they thought he was. After they repeated a few rumors going round, Jesus asked who they thought he was. Simon Peter piped up: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” (Mt. 16: 16) Jesus’ commendation showed that Peter had caught on to something important: it was not Caesar, whose neighborhood they were hanging out in, but Jesus, who was the real, true Lord. But what kind of Lord was Jesus?

It is significant that Jesus had wandered over to Caesarea Philippi, deep in imperial territory, before asking his disciples who they thought he was. After they repeated a few rumors going round, Jesus asked who they thought he was. Simon Peter piped up: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” (Mt. 16: 16) Jesus’ commendation showed that Peter had caught on to something important: it was not Caesar, whose neighborhood they were hanging out in, but Jesus, who was the real, true Lord. But what kind of Lord was Jesus? The Good Shepherd is a reassuring image. The shepherd is in charge and the sheep follow the shepherd’s guidance. When thieves and robbers and wolves come to threaten the sheep, the shepherd deals with them in no uncertain terms. Jesus’ claim to be the gate, the way in and out of the fold, gives us another reassuring image: some of us are in and certain other people are out, just the way it should be.

The Good Shepherd is a reassuring image. The shepherd is in charge and the sheep follow the shepherd’s guidance. When thieves and robbers and wolves come to threaten the sheep, the shepherd deals with them in no uncertain terms. Jesus’ claim to be the gate, the way in and out of the fold, gives us another reassuring image: some of us are in and certain other people are out, just the way it should be.