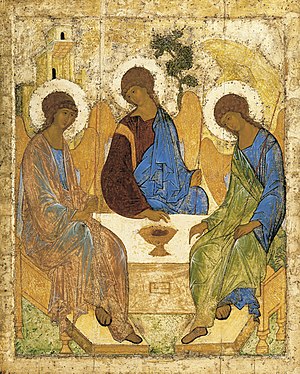

It is tempting to treat the Trinity as a mathematical problem. How can three be one at the same time? I don’t know much about math but I doubt that any mathematicians have solved that one. Let’s try imagery. St. Patrick is said to have used the shamrock to illustrate the Trinity. You have three leaves but it’s one plant so. . . well, historians have found no evidence that St. Patrick tried that trick anyway. Paintings with an old man, a dead Jesus and a dove may be moving at times but are crude theologically. Rublev’s famous icon, however, does succeed in making the three angels form a unified shape. More sophisticated is St. Augustine’s notion that the Trinity is implanted in human beings through the faculties of memory, intellect, and will. That’s one human with three faculties, but with our sense of individuality, not so say individualism, this analogy stresses the unity over/against the threeness. The classic formula of three persons in one substance is pretty abstract but at least it has a decent balance of Three and One.

As an alternate route, it might be worth thinking a bit about the dialectic of unity and diversity among humans. Each person is a separate entity but there are many instances where a deep unity is felt between two or more people. Marriage is the most obvious example where the two are said to be one flesh. The two are a couple. People talk about a couple being an “item.” But you still have two people. Friendship is another obvious example and here we could easily have three friends being closely united with one another. This analogy, too, is far from perfect as it veers towards plurality, especially in our individualistic age. Even so, what unity people experience with one another seems likely to be a faint but true indication of the Trinity. After all, if the Trinity teaches us anything, it teaches us that persons don’t have relationships, people are relationships. We shouldn’t give individualism the last word.

The mystery of diversity in unity at the heart of the Trinity speaks to what is arguably the biggest human challenge: learning how to encounter the other, the stranger, and to reconcile with enemies. One might object that since the three Persons are somehow one God, they surely aren’t strangers to one another. Presumably not, but sometimes the strangest strangers and bitterest enemies are those closest to us. Aren’t civil wars the most uncivil of all? What about the infighting within various church groups? And then there is what happens when two people who are “one flesh” tear each other apart. Offspring of a marriage may presumably be like the parents, but all too often these offspring become total strangers. Young Sheldon, an autistic child highly advanced in physics and math, is as strange as they come to his otherwise normal family. With the series having just ended, we see that the family, most profoundly his father, rose to the challenges of raising such a stranger for the most part, contrary to snippy remarks by the older Sheldon in The Big Bang Theory. One could interpret the Young Sheldon series as a long parable of struggling to meet the stranger, a stranger who at times is incomprehensible and at other times willfully difficult.

So, the persons of the Trinity. presumably far from strangers to each other, are the perfect example of close relations abiding in love without rivalry. Unbelievably more than that, they collaborated in the immense Act of creating a world of strangers to meet with and love and cherish. Not only that, but incredibly, these Persons seek to enter into deep union with all created strangers and continue to love these strangers when they become enemies. We aren’t left alone with our challenges to welcome the stranger and reconcile with enemies. We have Three Divine helpers and we have each other.

See also Trinity as Story and Song